Monkwearmouth Colliery 1991

Monkwearmouth Colliery was a major North Sea coal mine located on the north bank of the River Wear, in Sunderland. It was the largest mine in Sunderland and one of the most important in County Durham in the northeast of England. First opened in 1835, the mine was the last to remain operating in the County Durham Coalfield. The last shift left the pit on 10 December 1993, ending over 80 years of coal mining in the region. The Colliery site was cleared soon afterward, and the Stadium of Light, the stadium of Sunderland A.F.C., was built over it, opening in July 1997.

Monkwearmouth Colliery 1991

Zak Waters

56 pages

198 x 198mm

Numbered edition of 100

b/w digital printing

To buy the book click on Fistful of Books

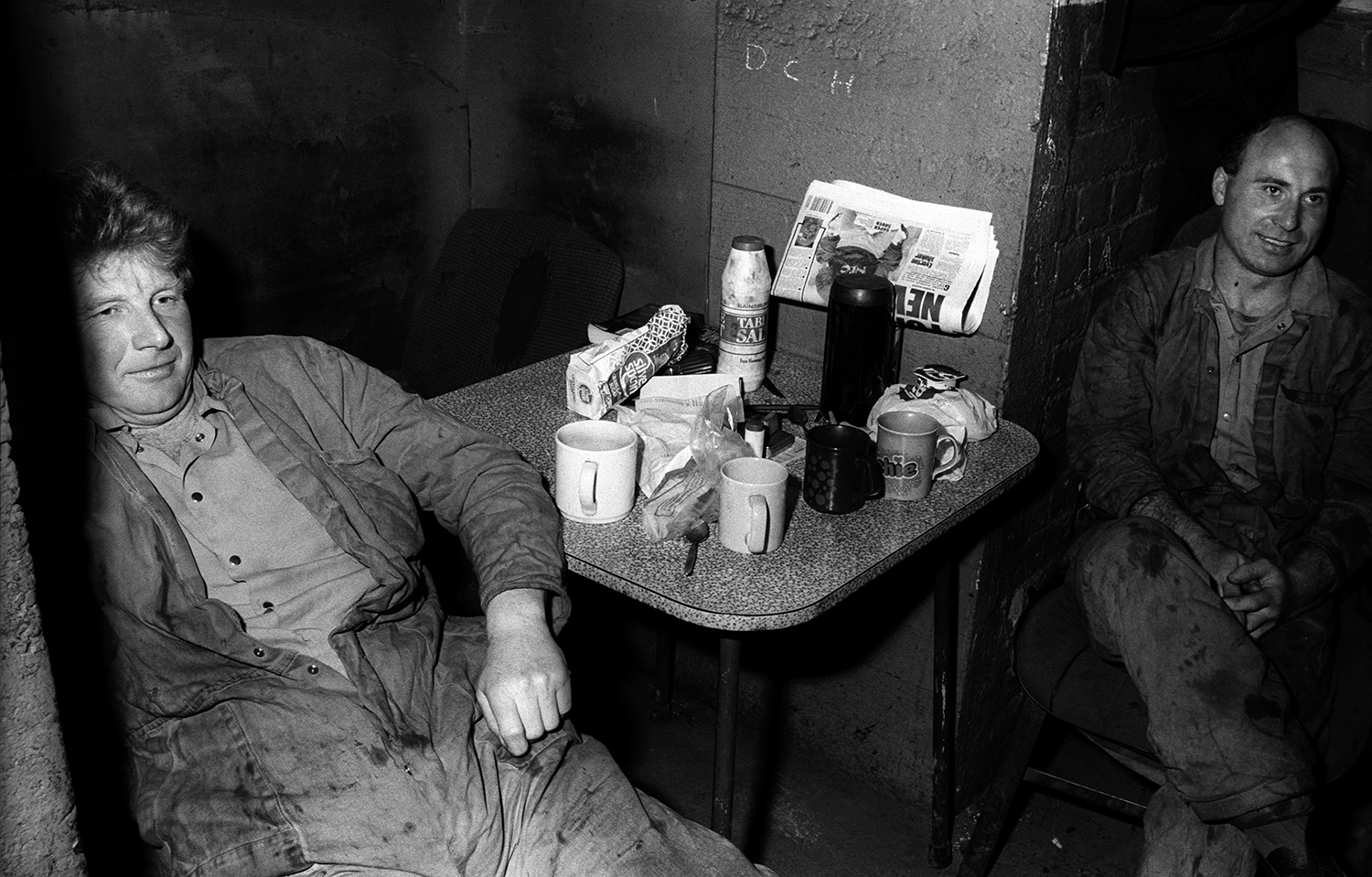

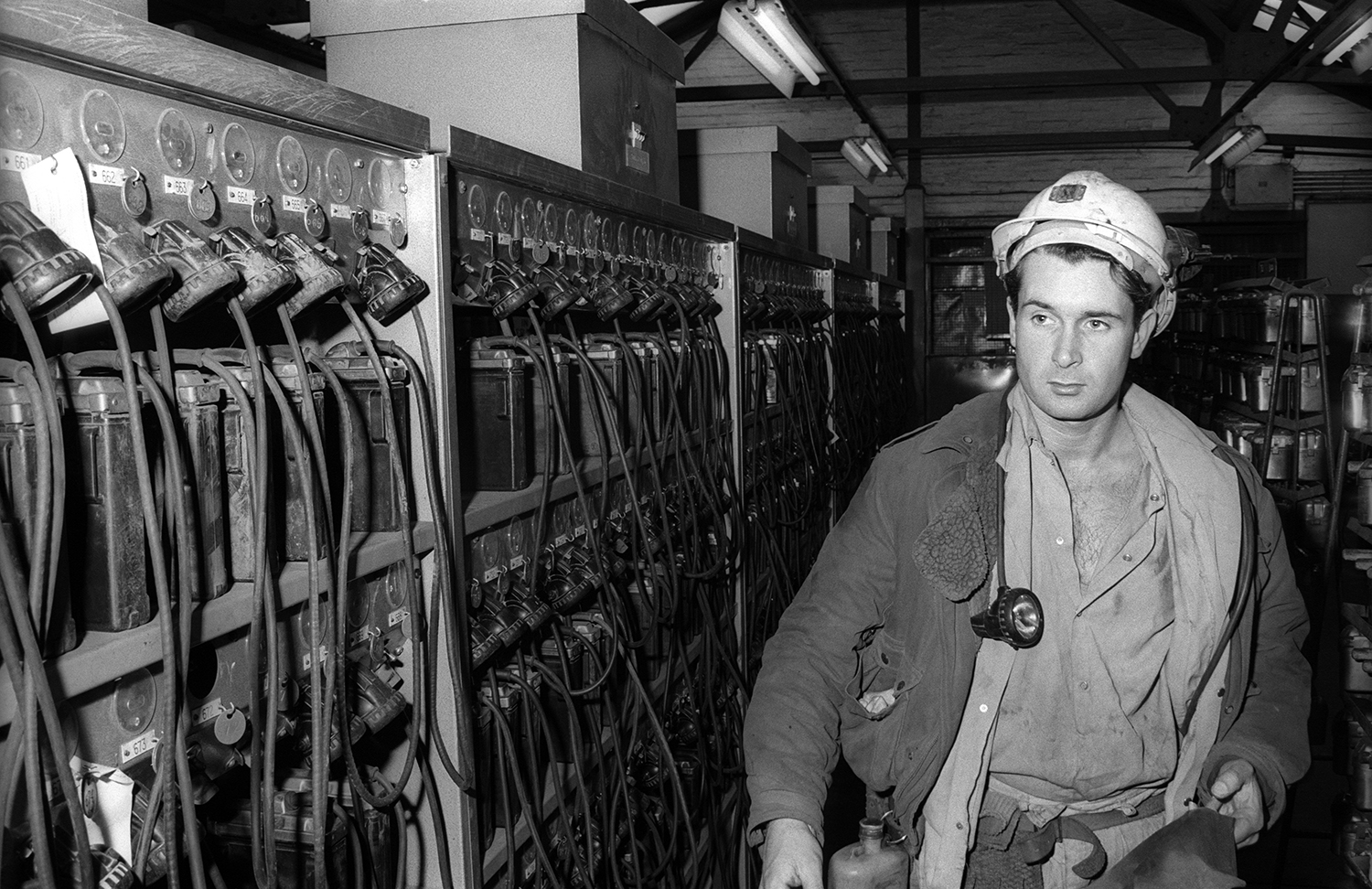

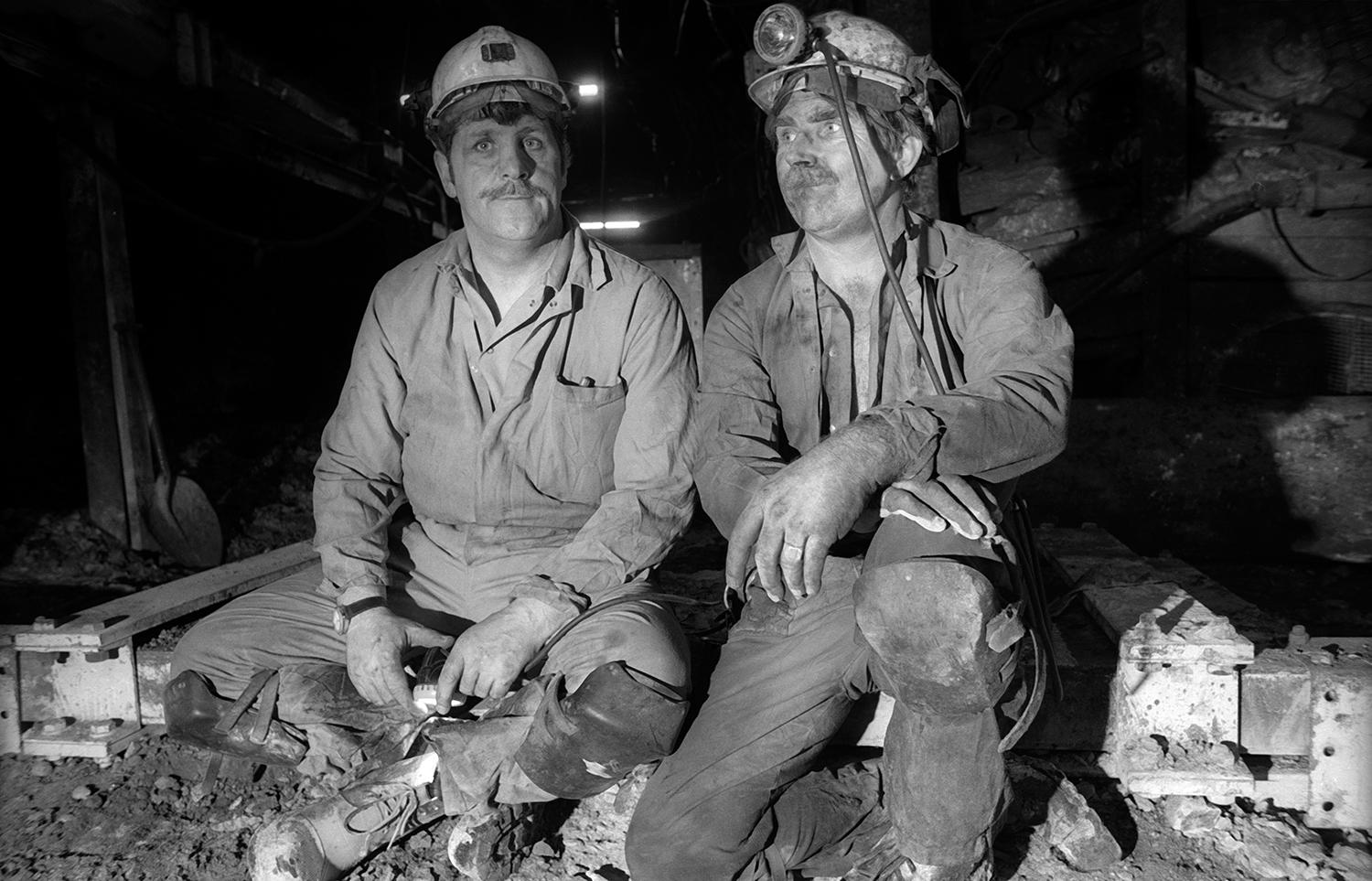

For a colliery worker at Monkwearmouth in the 1990s, life was a rhythm of shifts, grit, and tight-knit camaraderie shaped by an industry nearing its end. He arrived at the pithead before dawn or dusk, depending on rotation, collected his lamp and self-rescuer from the lamp room, and clipped a brass check to the board so the onsetter knew who was underground. The rattling cage dropped him fast through heat and damp, into a world of coal dust, steel, and hydraulic power where the longwall face crawled forward like a metal millipede. Down there, time was measured by the tramming of tubs, the surge of the shearer, and the thud of chocks setting.

Teams were everything. The deputy’s word carried weight; fitters, electricians, and face workers relied on each other for both output and survival. Dust suppression sprays hissed; roof supports inched forward; conveyors rattled; methane monitors blinked. Training films, safety briefings, and pithead baths were routine, yet the risks felt immediate: a shot-firing crack, a pressure burst, the sudden groan of strata. Wages were decent by local standards, but they were earned in sweat, bruises, and a body that learned to live with darkness, noise, and a constant film of grit on the teeth.

Above ground, the colliery anchored a community—union meetings at the welfare, pigeon lofts and football talk, family budgets arranged around bonus schemes and overtime. The 1984–85 strike still hung in the air as memory and argument; some scars inside the villages never fully closed. By the early ’90s, rumours of closure were constant background noise. Productivity drives brought new kit and stricter targets, but also fewer men per district. Each payday came with letters about consultations, redeployment, or voluntary severance, turning the canteen’s tea-steam into a fog of speculation.

A day’s work finished with the pithead baths: dirty set bagged, clean set on, a quick brew, then home to terraced streets looking out across the Wear. On rest days he fixed fences, coached youth teams, or took agency shifts, hedging against what everyone sensed. When the end finally came in 1993, the last shift felt like a funeral—helmets lined up, a brass band, handshakes that lasted a beat too long. Some men transferred; many took redundancy and tried for driving, security, college courses, or the call centre.

What remained was pride: in metres advanced, in a face kept safe and tidy, in mates brought home. The pit taught timing, teamwork, and quiet bravery. Even as the headgear came down, those habits stayed with him—etched deeper than the coal dust ever was inside.