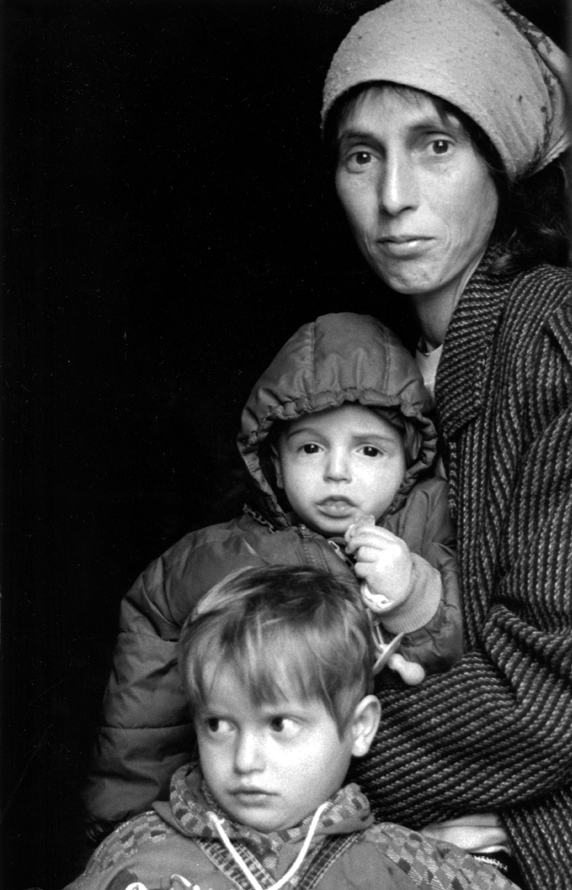

Kosovo Refugees – Macedonia 1999

The U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees estimates that more than 600,000 people, the vast majority of them ethnic Albanians, have left Kosovo since NATO began its air assault on 24 March 1999.

In Macedonia the estimated figures of refugees is in the region of 132,500 (MSF).

Kosovo Refugees – Macedonia 1999 56 pages 198 x 298mm Numbered edition of 150 b/w digital printing Published by Fistful of Books(2020)

Buy the book:FISTFULL

Dimal 25, a student studying German from Pristina.

“The situation was getting worse day after day. We couldn’t get out of our flat. We stayed inside for more than a week. The buildings were surrounded by paramilitary soldiers wearing a uniform of a kind I have never seen before: a type of paramilitary uniform with masks over their faces. They were yelling and screaming. My whole family had to leave immediately. We jumped in our car and drove to our cousin’s house in another area of Pristina, thinking we could stay there for a short time. On the way, the Police arrested us and demanded 100DM to let us go. We stayed at our cousin’s flat for one week with three other families, around 30 people in total. No one could go to work. The main problem was the food stock.

For the first few days we had enough food, but going out was really dangerous. We had to be vigilant day and night. More and more people were leaving, we had no news of them and panic was rising. Phone lines were cut. We were consumed by fear. As long as electricity was available, we watched the news continuously.

The tension was increasing.

It was really hard to leave the city we knew inside out; the smallest streets and different areas, but my family wanted to leave and I didn’t want to be separated from them. We planned to leave for Macedonia early next morning. We heard that cars were queuing for more than 20 kilometres at the Macedonian border and that everything was being looted. We decided to flee by train. We drove towards the train station at 7.00a.m. Many women and children were walking in the same direction. Serbian policemen and soldiers were everywhere, yelling at us and screaming insults.

At 7.30 a.m., thousands of people were gathered at the station. The train arrived at 10.10 a.m., already packed. My seat number was 94; I will never forget it and hope that one day I will return to Kosovo with the same seat number. Everyone was infinitely sad.

On the train, I saw two Serbian soldiers. They went into one compartment, beating people, breaking one man’s teeth and tearing up people’s personal identity papers.

The journey took 2 hours.

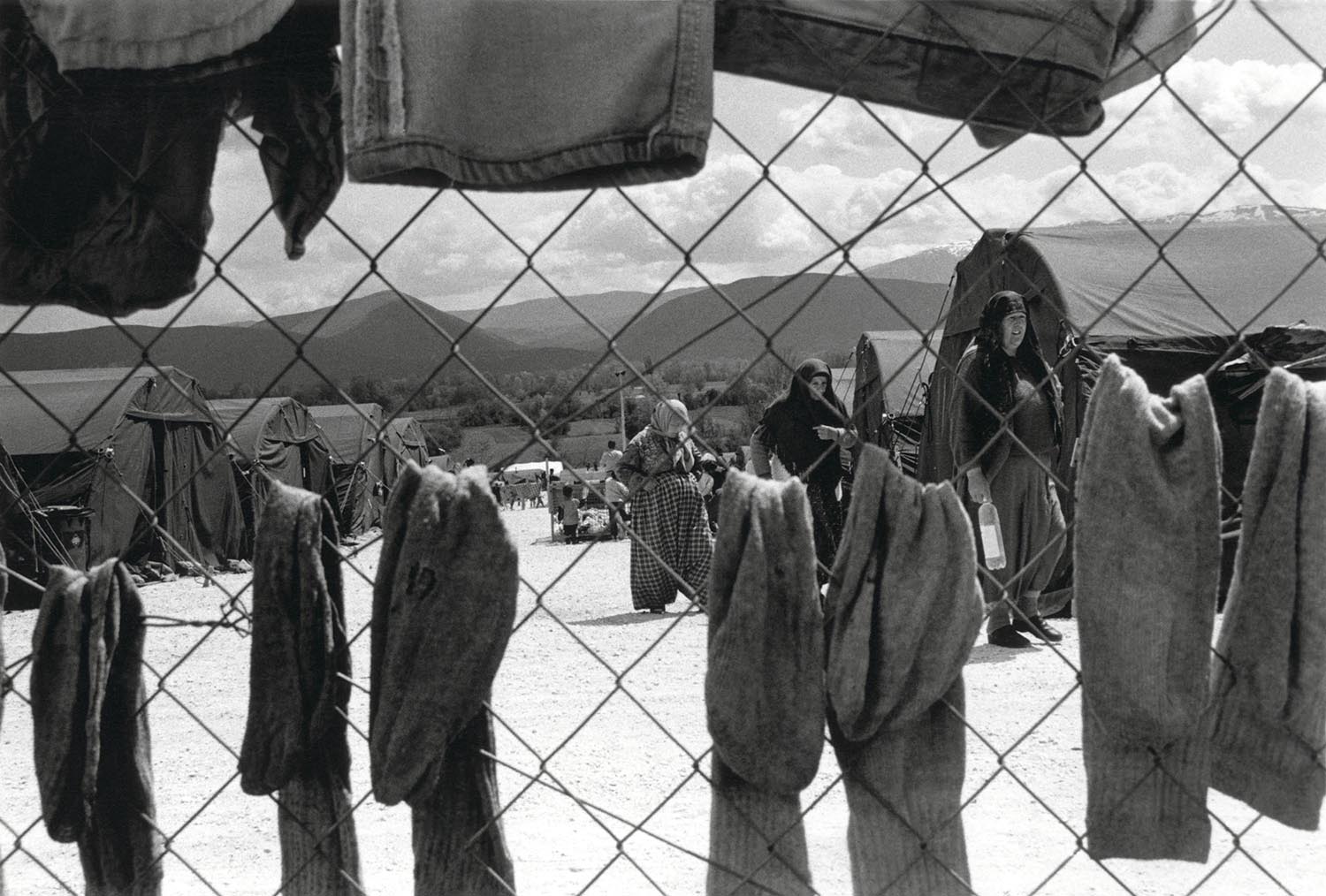

The train stopped at the border after Ellesal, or Jankovic, as the Serbs called it. We got off the train, but the Serbian’s said that area was riddled with mines…so everyone tried to keep on the rail tracks, there were so many of us that some had to walk off to the sides: fortunately, nothing happened. We walked for an hour before we arrived at the no-mans land of Blace. There, we saw many people in a field. We recognised some people from Pristina. The situation was disastrous. We had to protect ourselves in case of rain. We found a piece of plastic to make a shelter. It was too small for all of us.

During the night we went to look for blankets to put on the ground. Food was supplied to the camp by tractors. When a tractor arrived, everybody was jumping on it. It was a strange feeling seeing people behave like that.

Everyone had lost everything and just wanted to survive.”

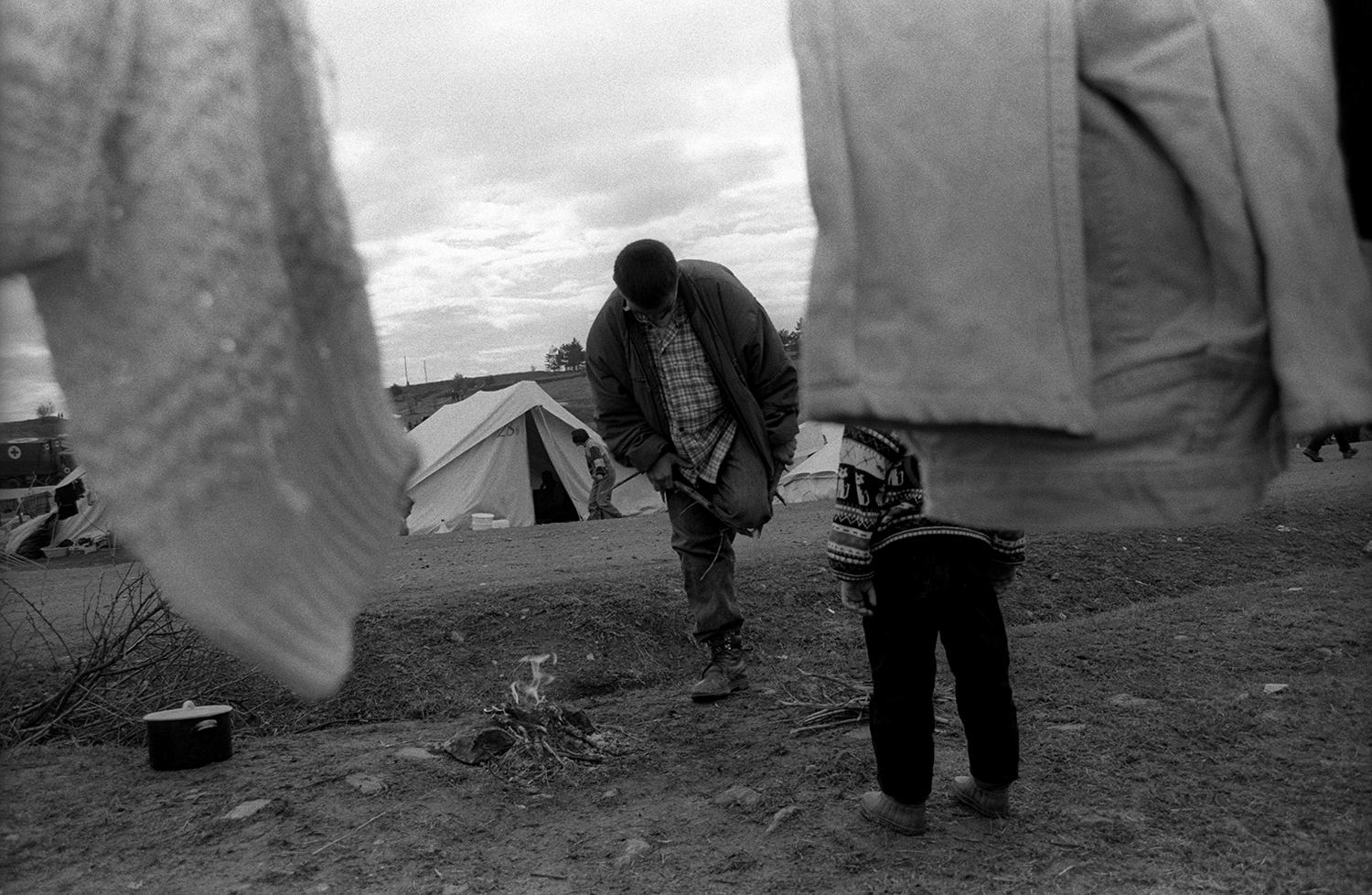

I saw people with whom I used to drink in Pristina; they were literally leaping at a piece of bread. The camp was enormously big, without any sanitary facilities. It was very cold and impossible to sleep. I was lucky to spend only one night there. At night, people were picking up wood and making fires to warm themselves up and at least be able to see something. Tents were set up in total disorder. Everything was chaotic. To cross the camp was impossible. One could easily walk on somebody’s head or hands. Many people didn’t have any shelter. They were almost sleeping in the mud as it had rained a few days before. To stay in the camp was a real hell.

I was lucky all the way through.I managed to catch the last train from Pristina.I stayed only one night in Blace, but what about the others?

Fatma, an agronomist from Pristina

“At first, we thought everything would be over in two, three days. Then we heard that people were being killed by the police, thrown out of their homes. We were afraid that we might be deported. It was hard to stay inside the house, unable to move, to go out in to the streets. My father, 76, went out to buy something and saw all the cafes and shops in ruins. These days were just awful. We could not fight, we had no weapons. We were afraid of the reaction of our Serbian neighbours.

It was better to be a cat, a dog or any other animal in Pristina than to be Albanian.

I felt that it was becoming more and more dangerous to stay, above all for men and young people: our whole family left together, my parents, my cousin, his wife and his children.

At the station, there were policemen. We heard people screaming in the streets, people being turned out of their homes. Pressure had now risen too high to wait to be thrown out. Everyone wanted to survive. The able-bodied were carrying the handicapped and even the elderly were leaving. We got on a train with some thirty carriages. More and more people got on every minute. One man handed me over his son through the window from outside, saying to me ‘Take him or they will kill him’. Then the train left.

In Malishevo, we only saw dogs and policemen. Young people were hiding in the train, for fear of being caught. The towns were completely deserted, like ghost towns. This was really the most frightening thing of all. We arrived at the border and were told to get off the train. We had to walk on the track in 3’s, as we were told the fields were riddled with mines.

We suddenly found ourselves at the entrance to Blace. People had red eyes and were shivering with cold. I thought to myself: Is this like hell?

What is going on?

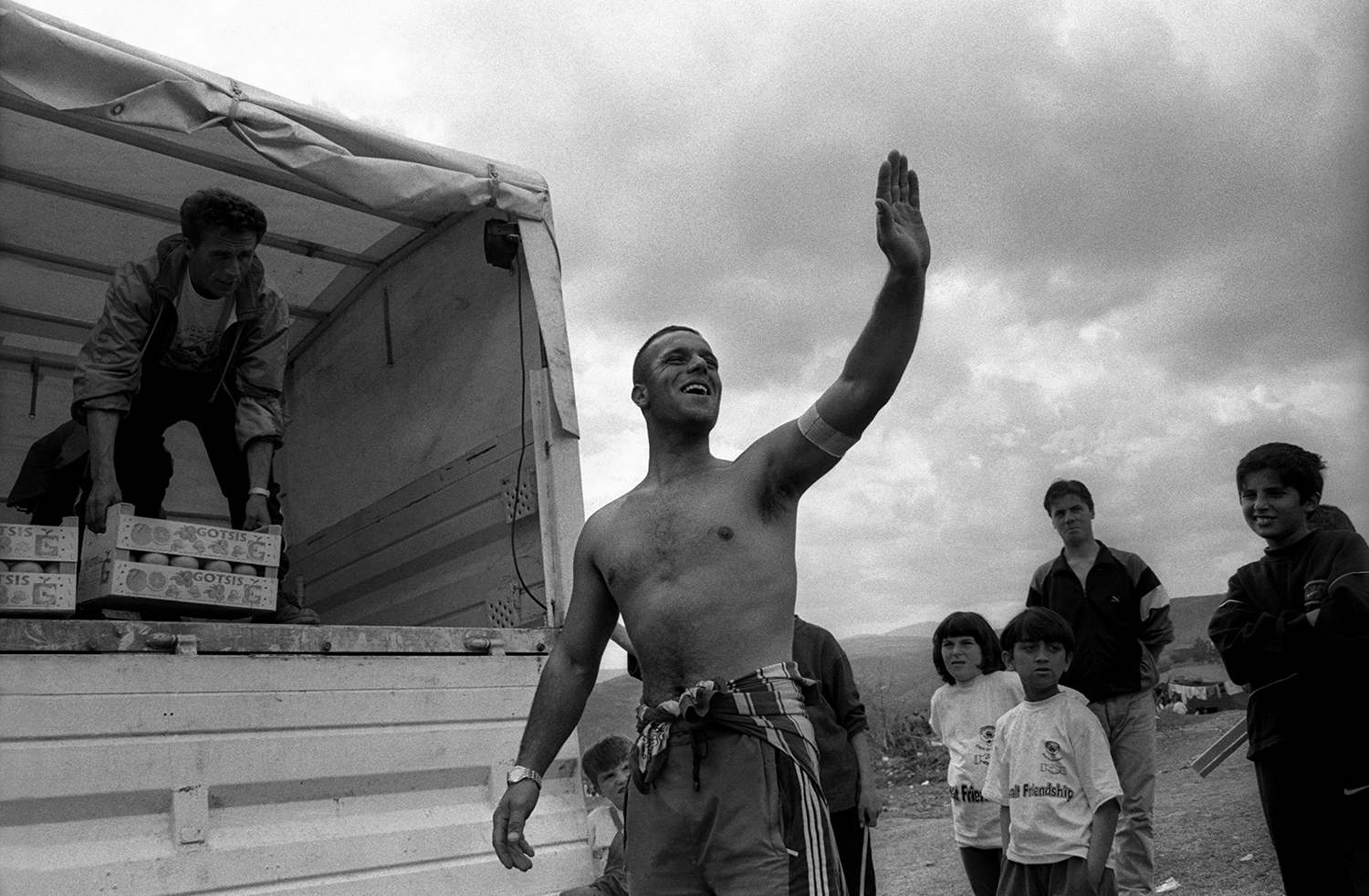

After 100 metres, we saw a sort of town with makeshift tents, a town like in the Middle Ages . I saw a person who knew me who said ‘Don’t worry. You will stay for a week or two’. I managed to find a little bit of bread and then some milk for the family. Food was distributed by tractors driving across the camp. People were running after them, almost getting run over. This was really upsetting. There were some incidents, some injured. People were acting as though they were mad.

There were no toilets people just went wherever they could.

One guy said ‘Ah, this is my bread’ and by the time he returned to his place, all he had left was a tiny piece in the hollow of his hands. Everyone had taken the bits away.

Many people were sharing. More than thirty people died while I was there, elderly people or babies. The Macedonian’s were very tough as well. They would not let pregnant woman past, or if they did it was without their husbands.

After two hours in the camp, I was like everyone else. I was running after the tractor. We still did not have plastic foil for a tent. I managed to snatch some from a passing tractor and quickly pitched a tent with my father, but it was very cold. We stayed by the fire to warm ourselves up. We heard children crying at night yet we could not do anything. People were talking while sitting around their fire places……..talking about what they would do if they were to return, hoping the country would be free.

The next morning we joined the queue in the hope that we might be able to leave the camp. It was 6-7 a.m. My cousin had some bags, I told him that he had better leave all his belongings in the camp and carry his children in his arms, so that they would let him through. I was happy. I only needed to look after my 76 year old father, my 61 year old mother, my eighteen year old niece and my 24 year old sister.

I managed to cross the border twice, carrying sick people for the Red Cross, but my family could not get through. My mother fell ill and was eventually allowed to leave with my sister and my niece. I was left only with my father. I beseeched the police for five hours before they let the elderly man pass, who was completely lost without his family. He finally got through, but he started going back, as he could not find our family and was afraid of being on his own. I told him ‘Stay there. Don’t come back. That will be too tough.

Finally I managed to get past, thinking of my father all the time. I called him. Then, all of a sudden I saw them all.