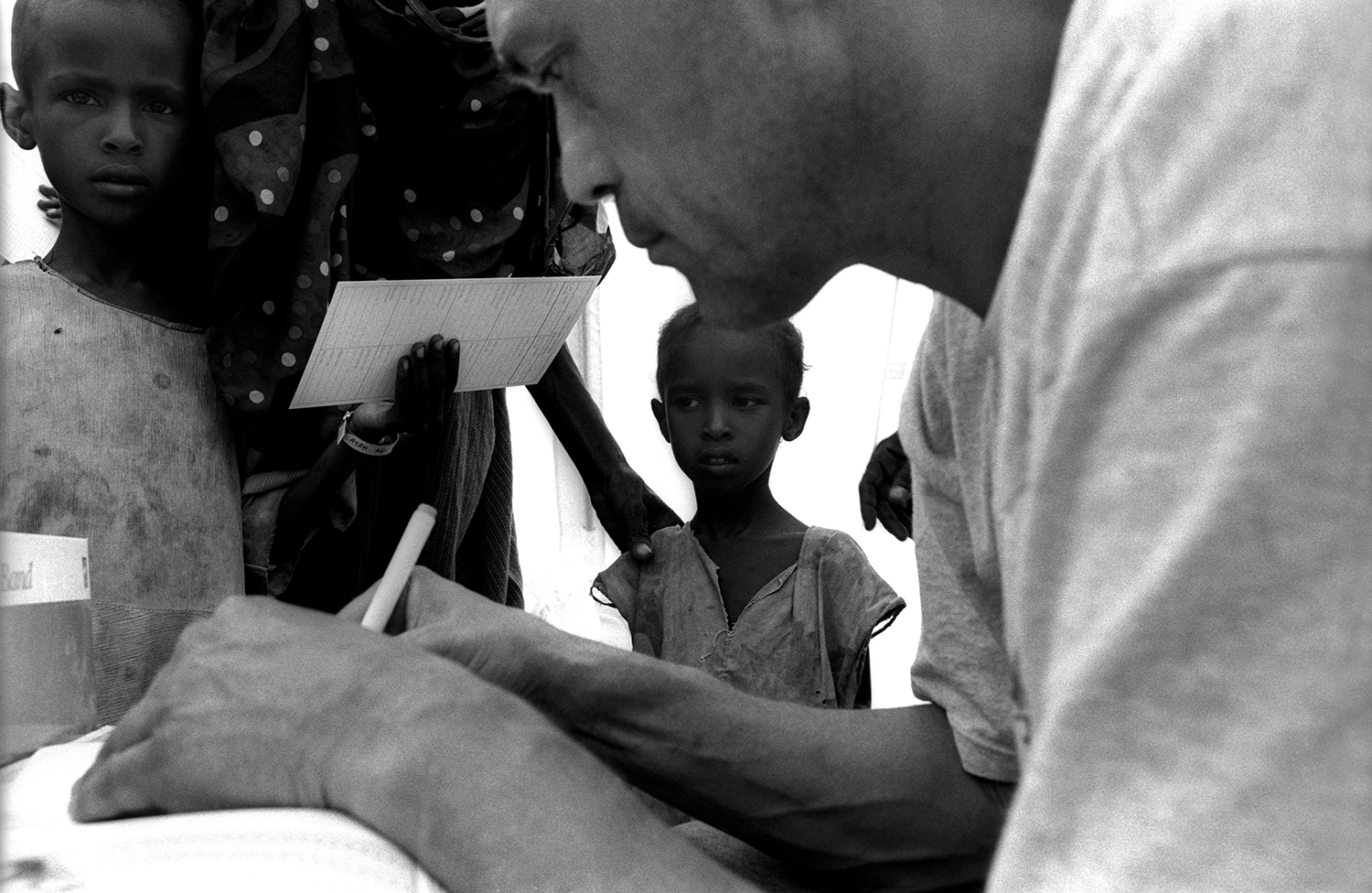

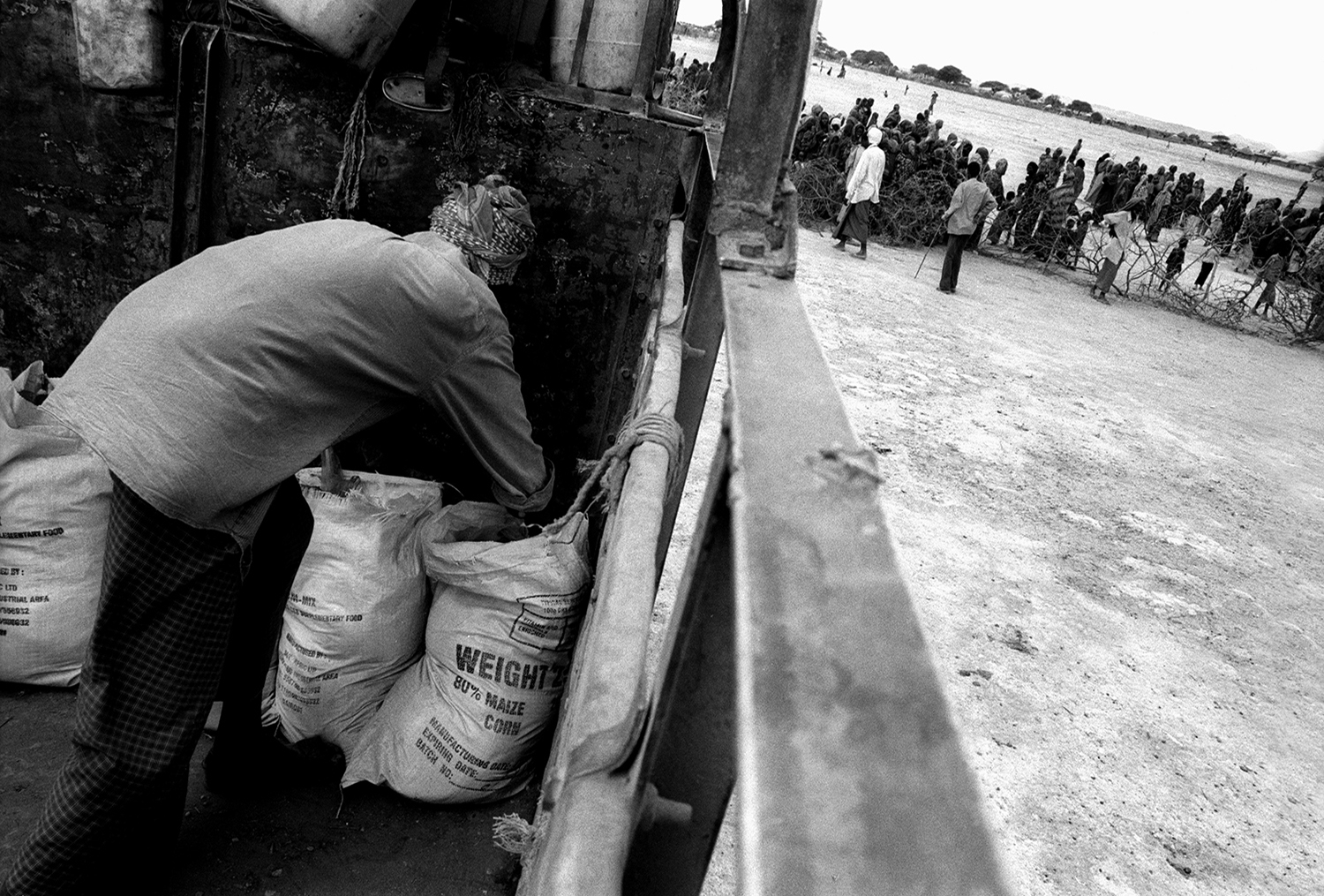

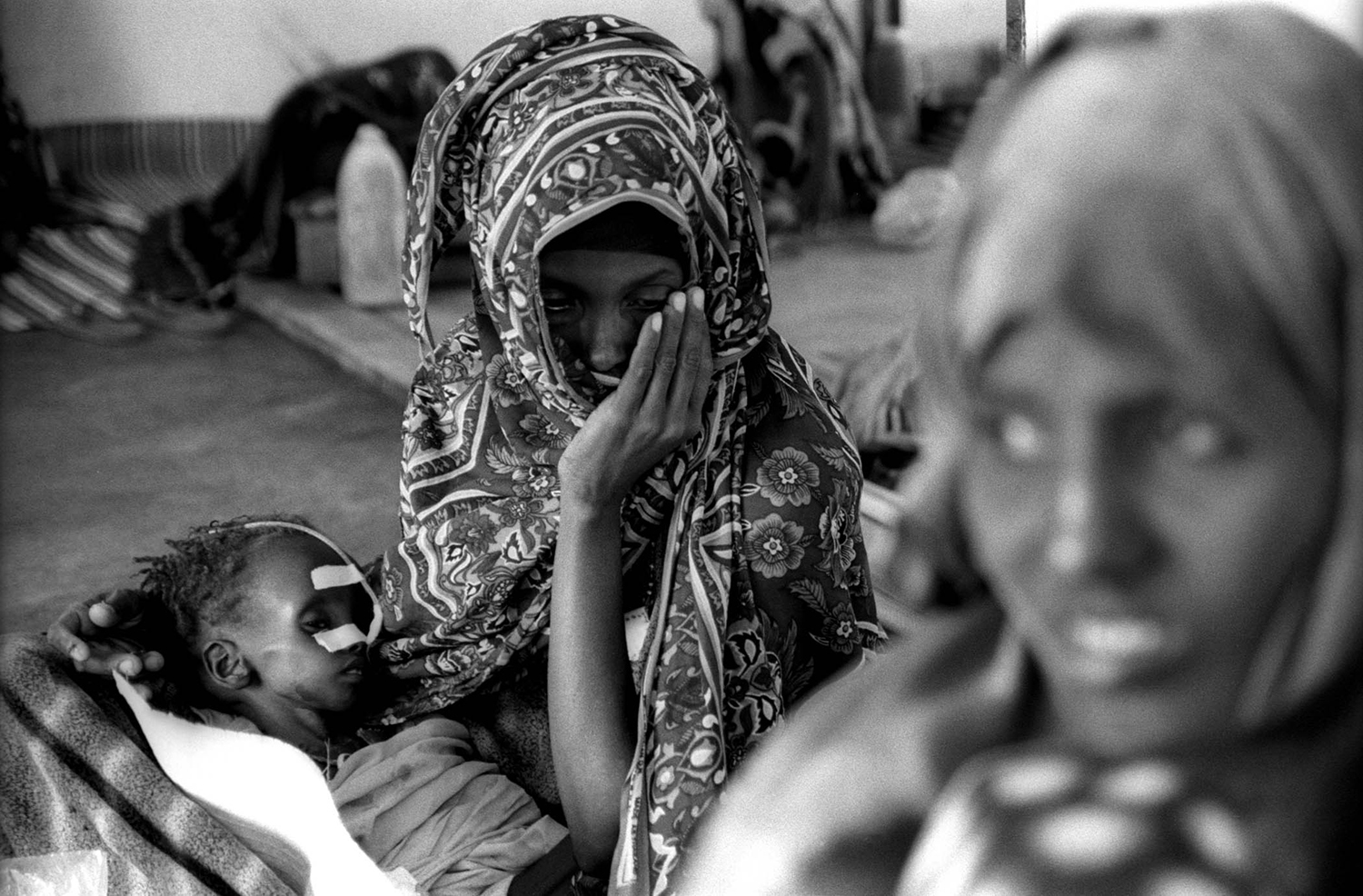

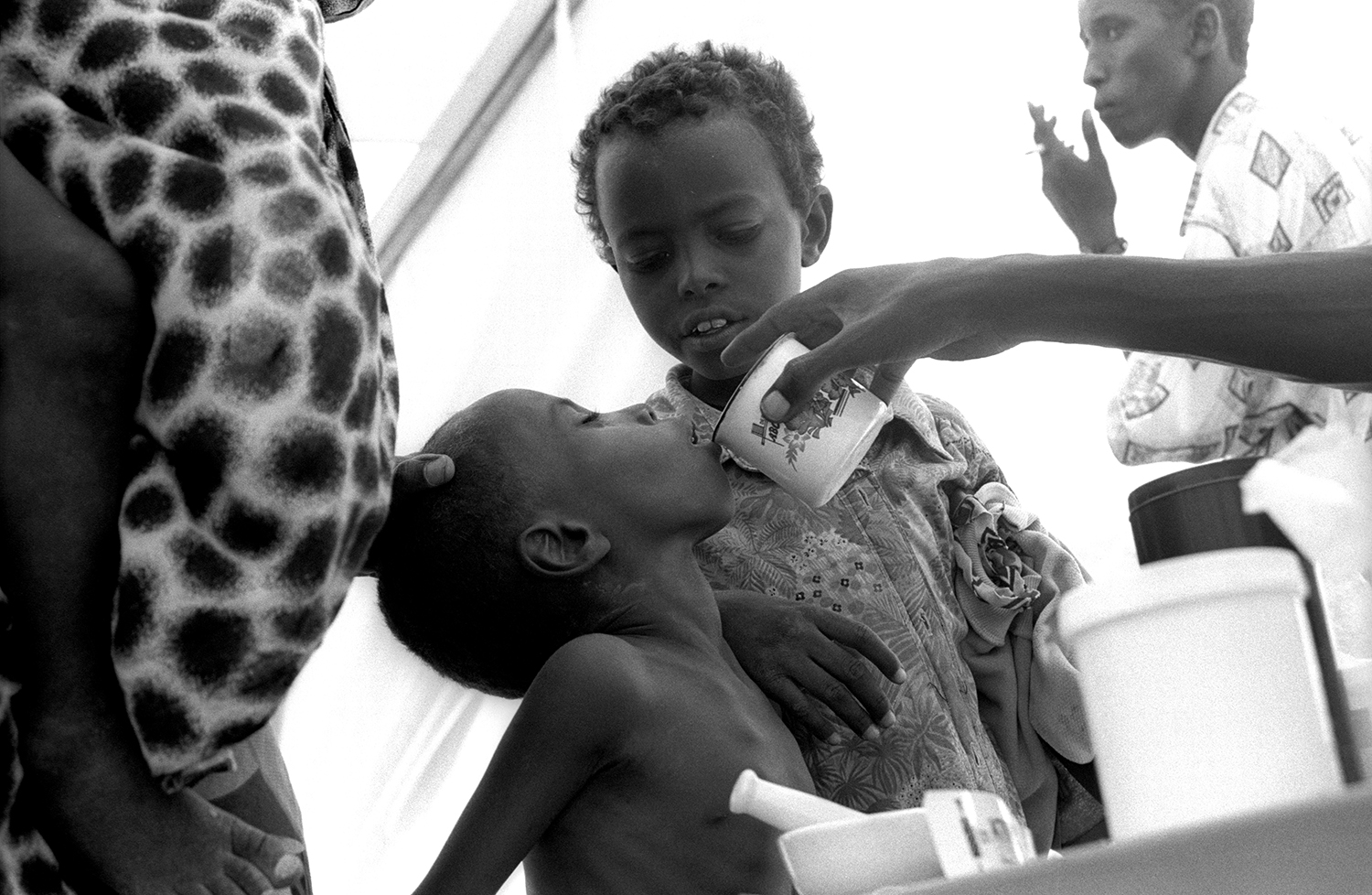

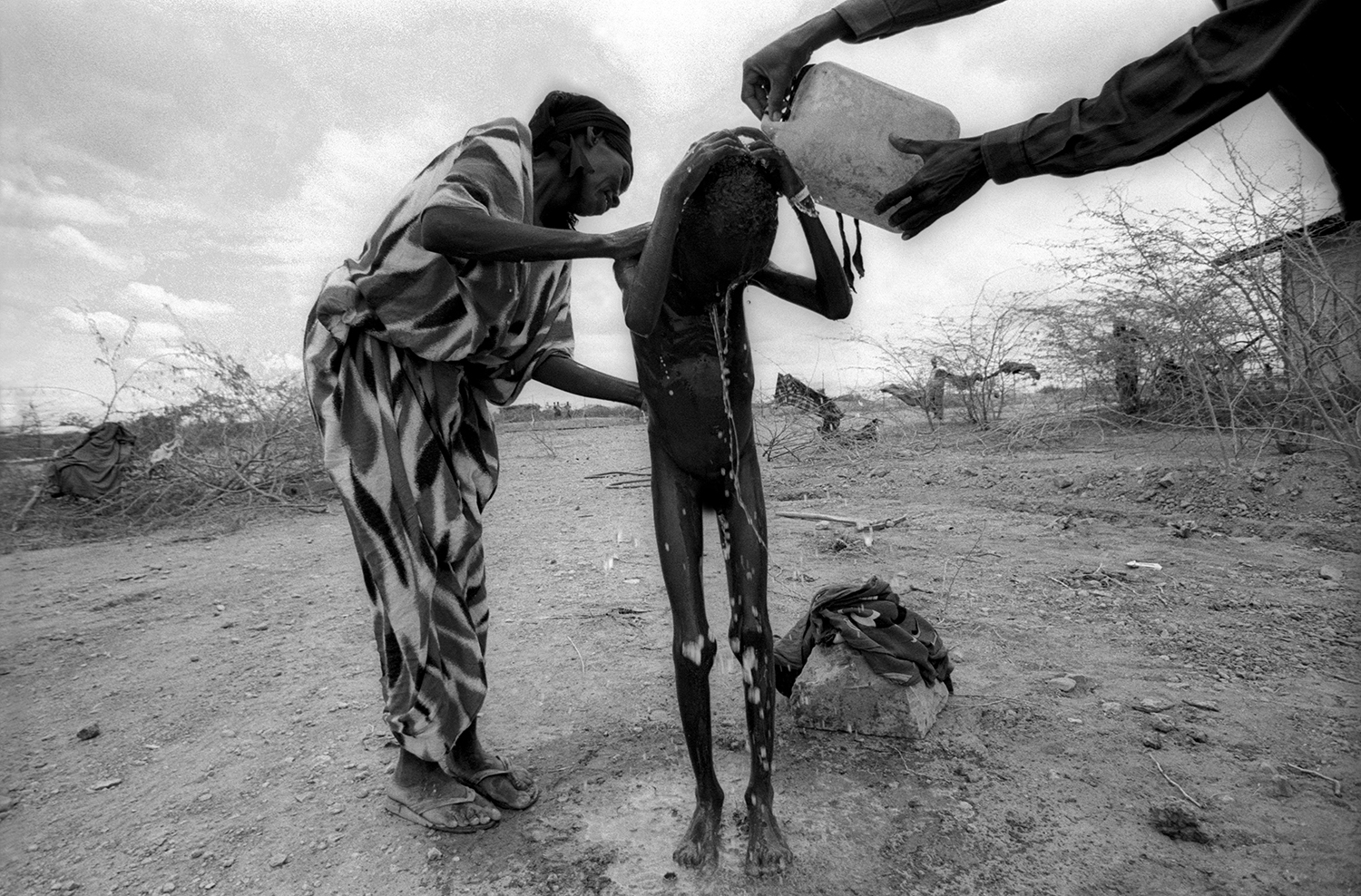

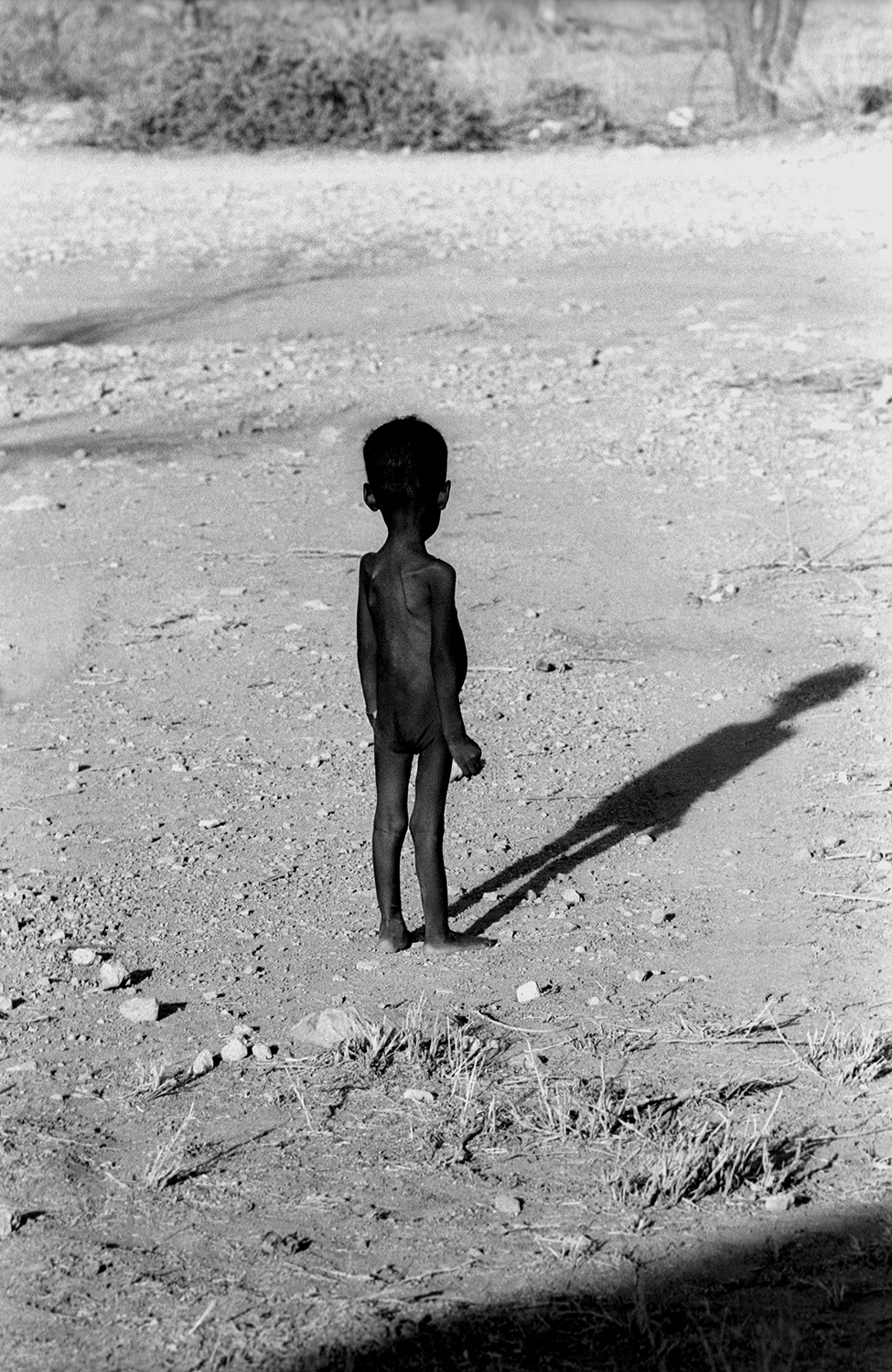

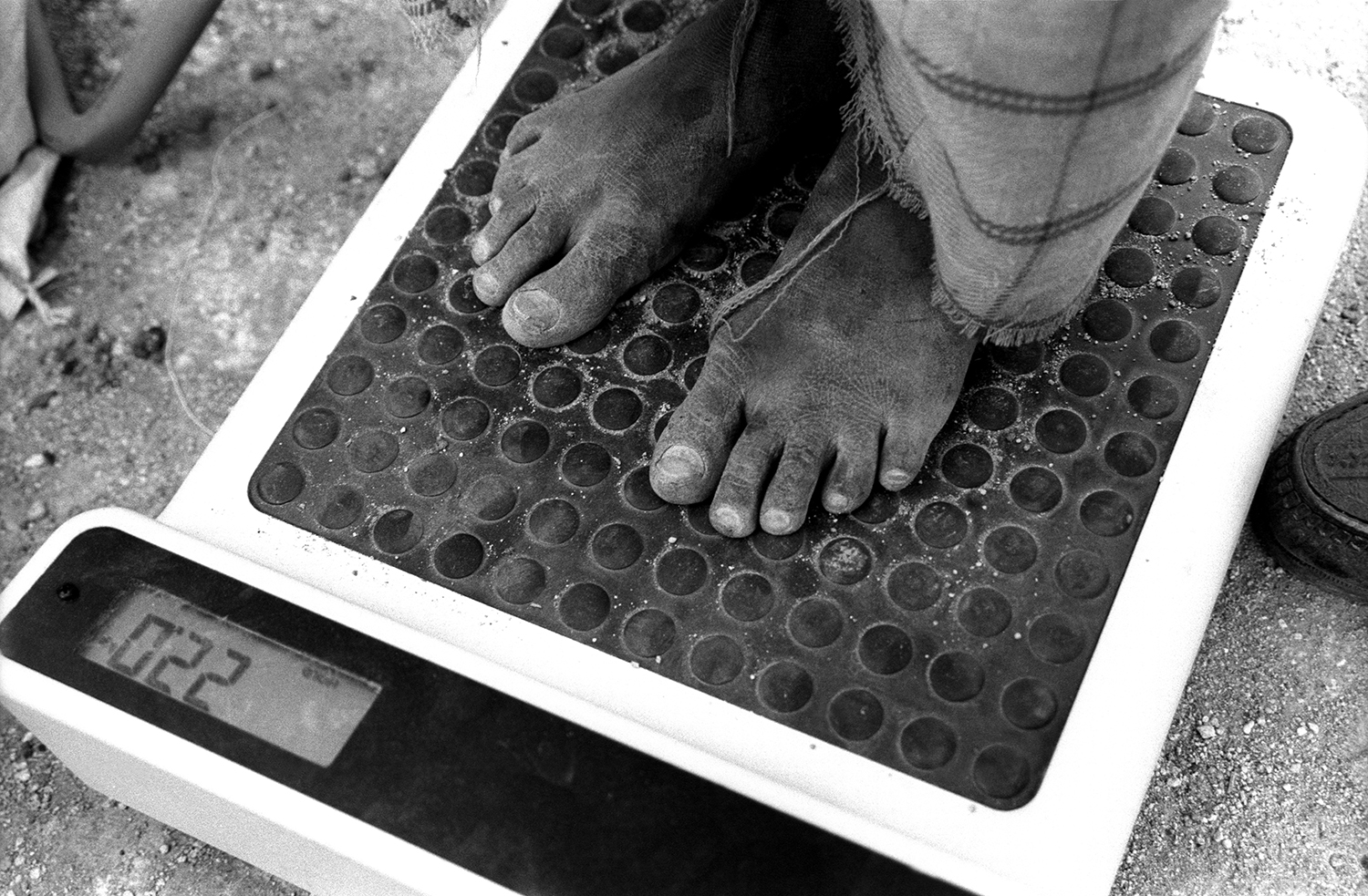

Ethiopia: Famine in the Ogaden. A severe drought affected 13.2 million people in 2002/2003. Program data showed that thousands of adults and children died despite the large scale humanitarian response. However, despite the drought being the most extensive in the country's modern history, there was a higher child mortality in drought-affected areas but no measurable increase in child mortality amongst the general population. Household-level demographic factors, household-level food and livelihood security, community-level economic production, access to potable water, and household receipt of food aid were predictive of child survival. The latter had a small but significant positive association with child survival.

The origin of the term Ogaden is unknown, however it is usually attributed to the Somali clan of the same name, originally referring only to their land, and eventually expanding to encompass most parts of the modern Somalia Region of Ethiopia.

During the new region's founding conference, which was held in Dire Dawa, Ethiopia in 1992, the naming of the region became a divisive issue, because almost 30 Somali clans live in the Somali region of Ethiopia. The Somali nationalist group the Ogaden National Liberation Front (ONLF) sought to name the region ‘Ogadenia’, whilst the non-Ogadeni Somali clans who live in the same region opposed this move. as the naming of the region where there are several Somali clans as ‘Ogadenia’ following the name of a single clan would have been divisive. Finally, the region was named the Somali region.

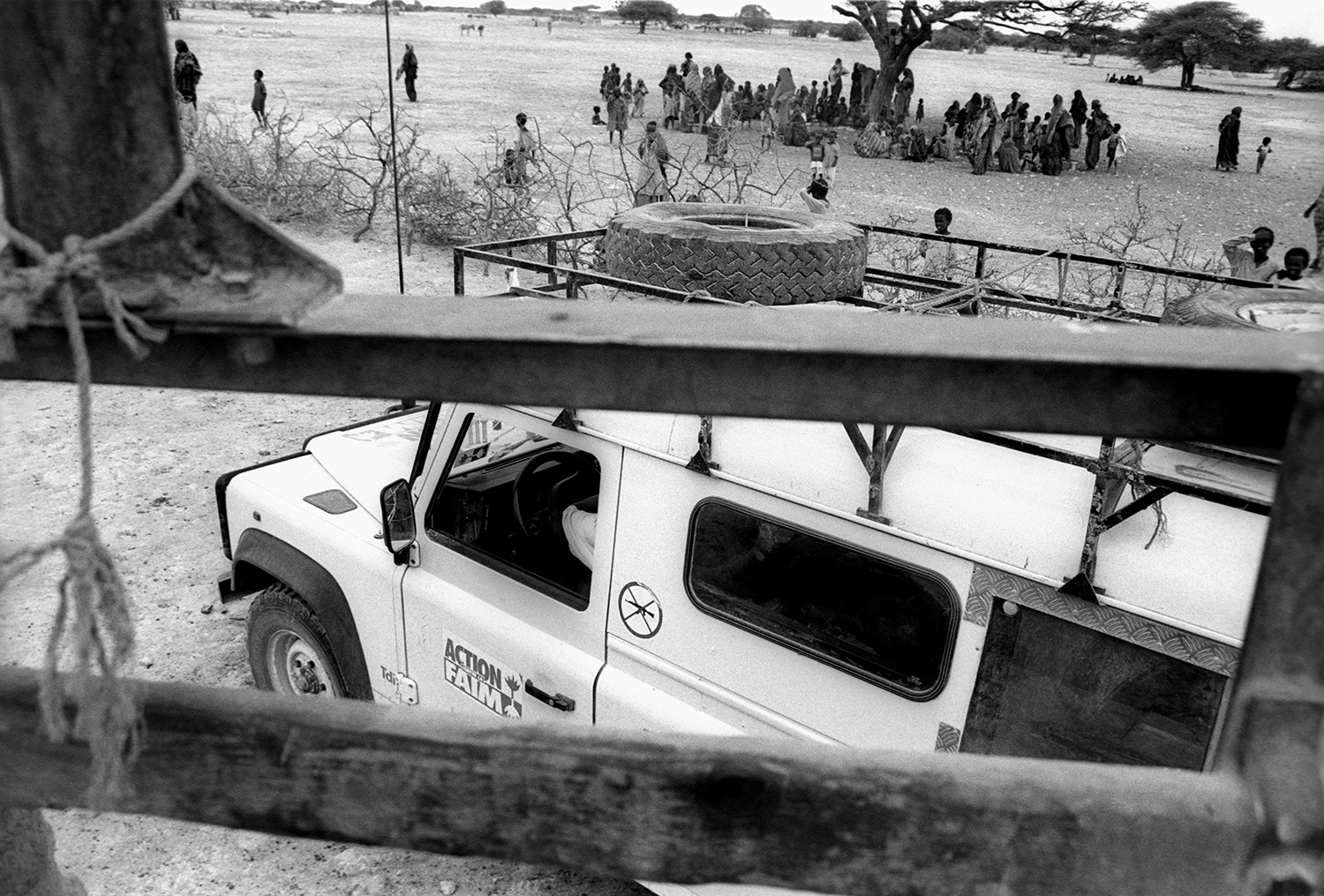

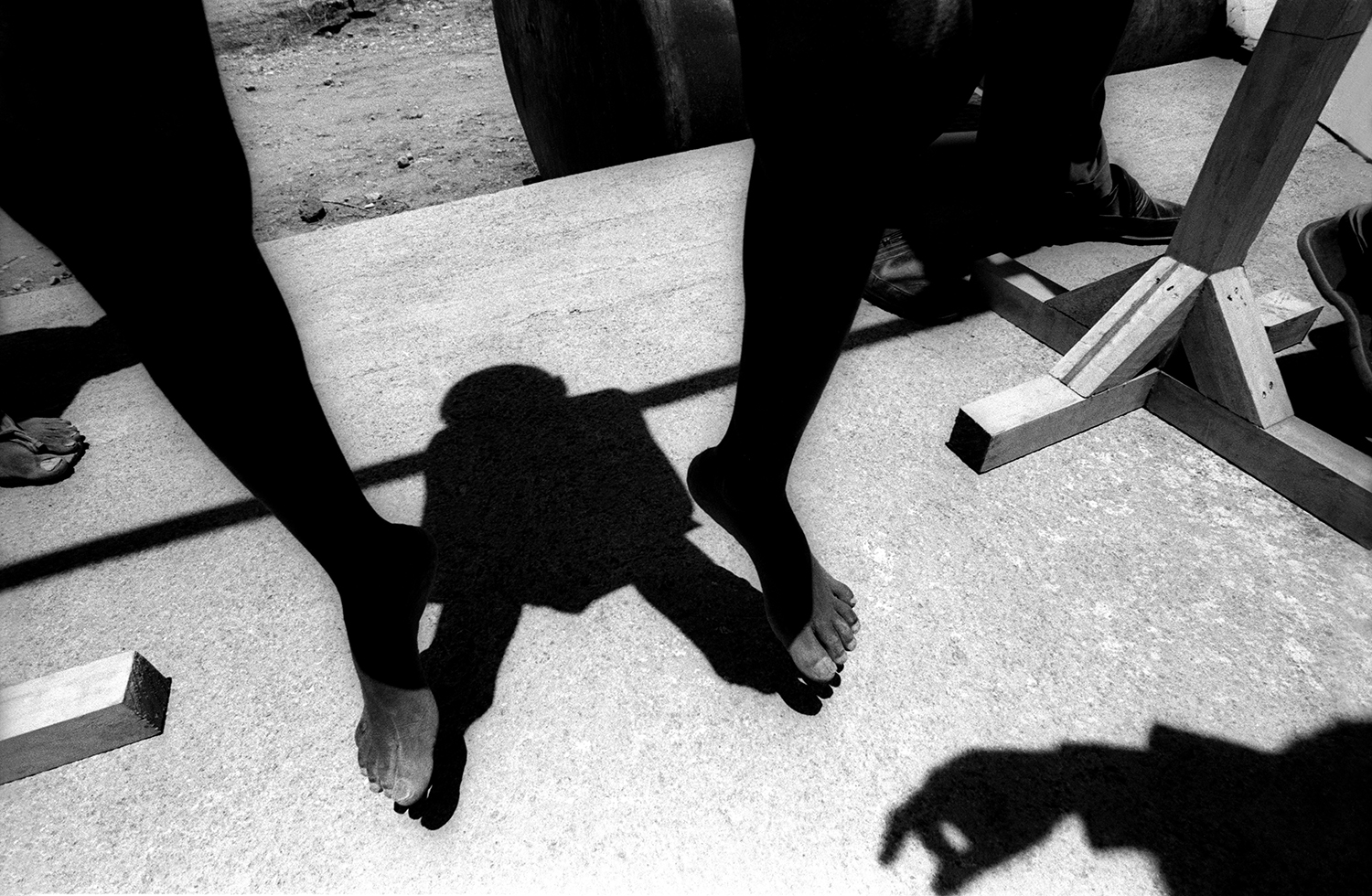

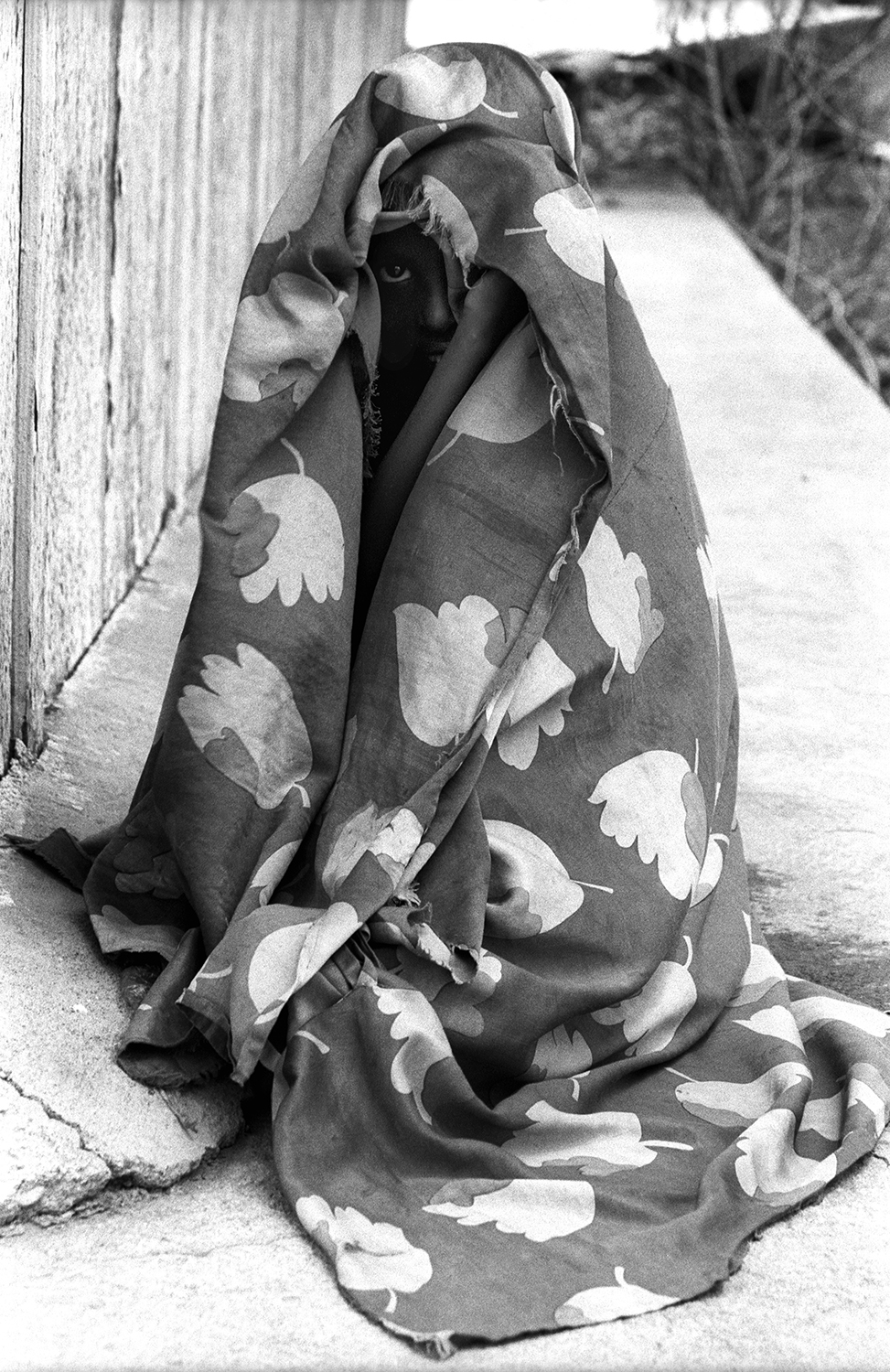

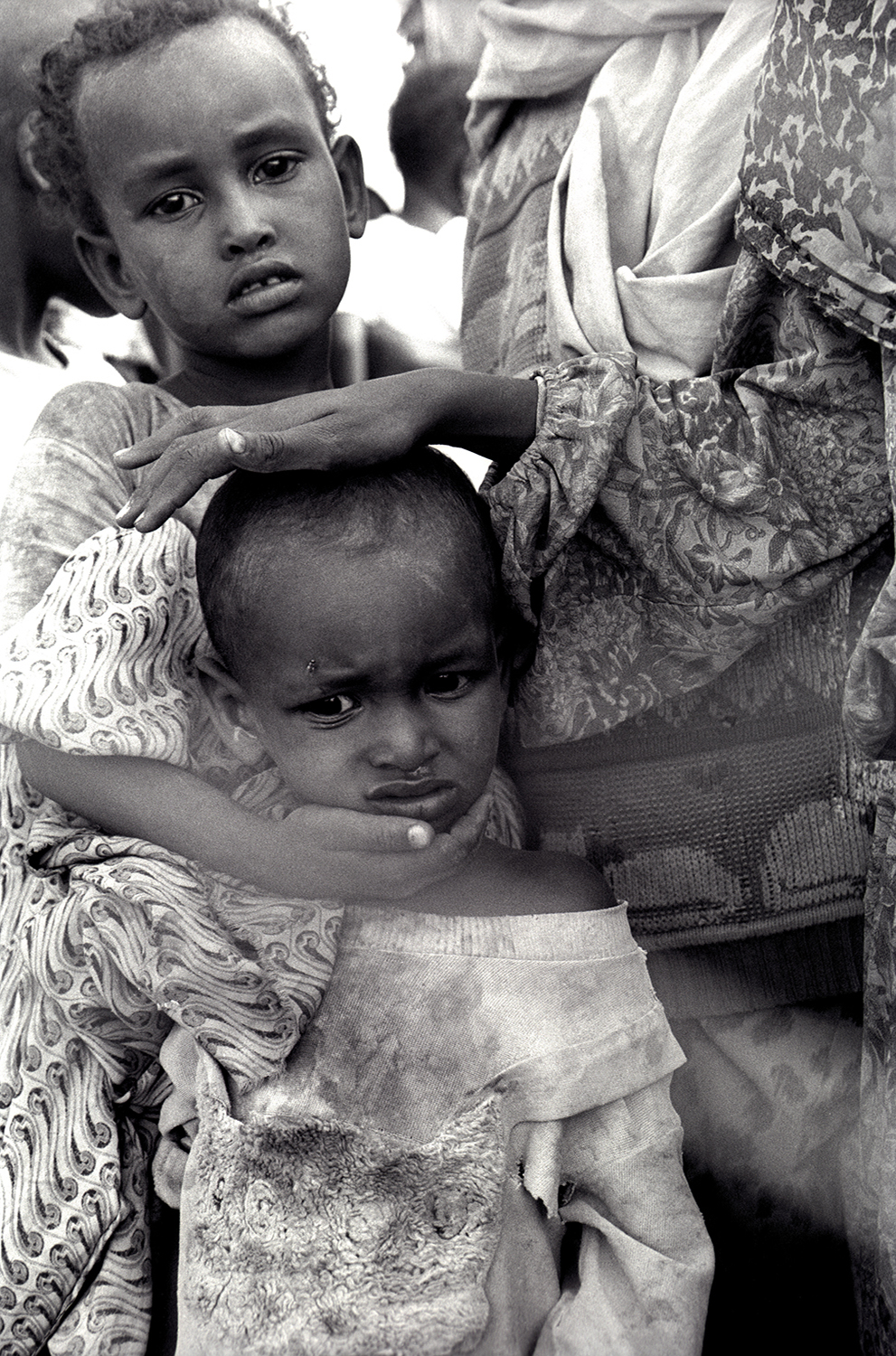

A number of these images were used worldwide to help raise significant funds for the feeding centres and the French ACF team in the Ogaden region.

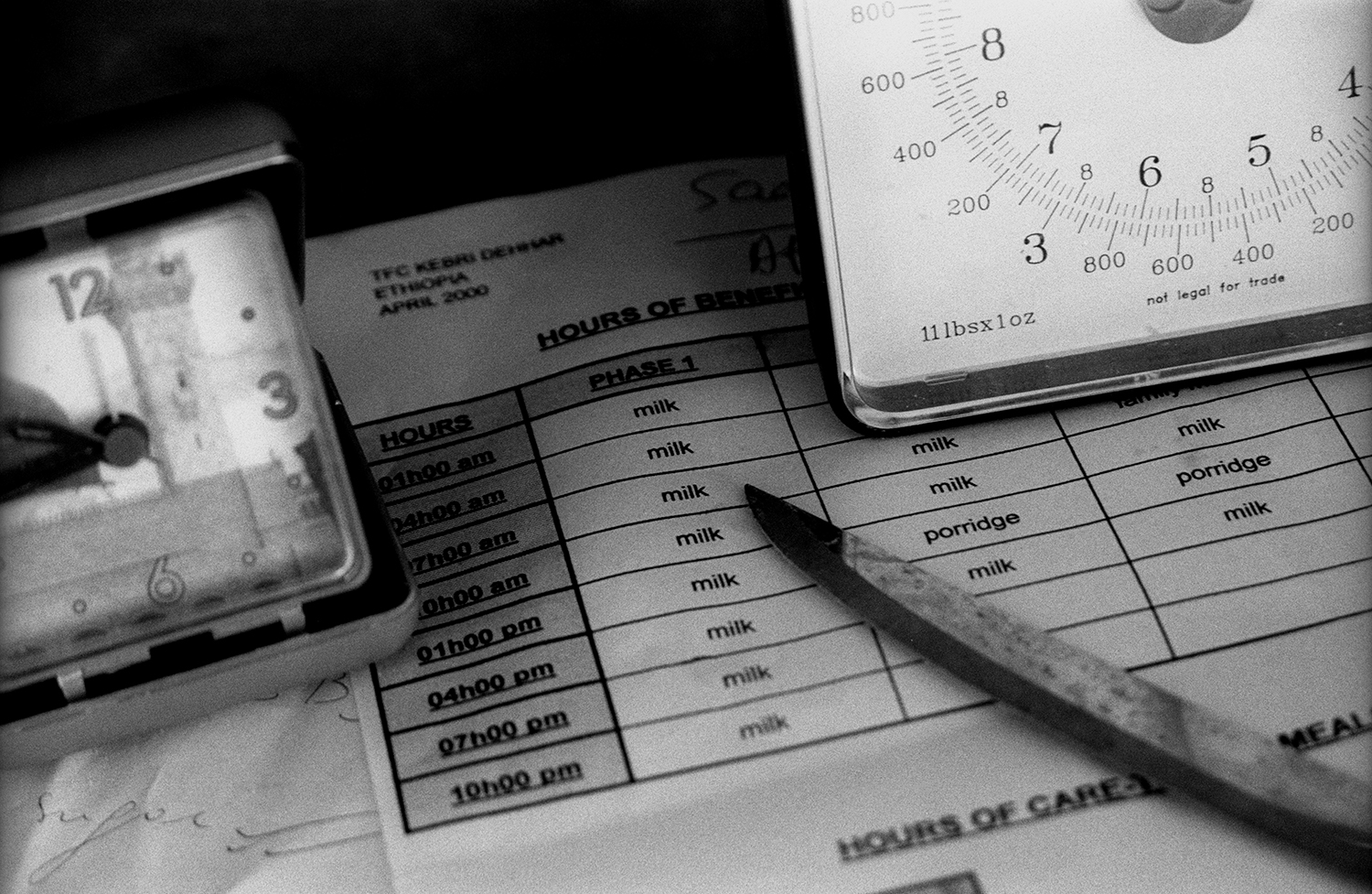

Action Against Hunger UK (AAH) assigned me to produce a series of images for an emergency food & medical appeal during the 2000 Ethiopian famine in the disputed Ogaden region between Ethiopia and Somalia. I was to team up with Action Contre la Faim (ACF), the French of the AAH team in Addis Ababa, the capital of Ethiopia.

At the time, the Ogaden National Liberation Front (ONLA) fighting meant that the region was a no-go zone for British and American workers, though a single French NGO, Action Contre La Faim (ACF), was active in this area and had ventured further than Gobe, where all the other NGOs were based. Now I was to join them.

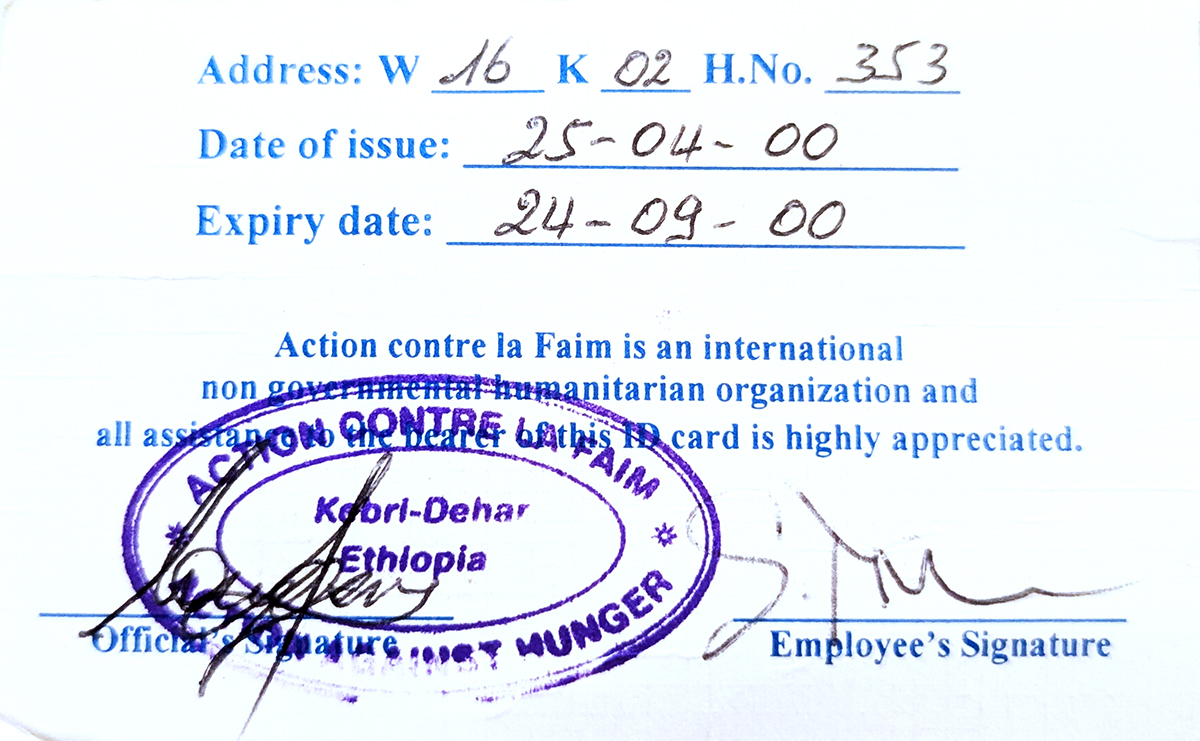

ACF’s aim was to reach the nomadic tribes that lived and roamed the Ogaden plains. So, the only way for me to access this part of the Ogaden was to obtain some forged paperwork. My new paperwork and ID identified me as a French water engineer called Sebastian—and after six separate storm-dodging flights, I was dropped off on a remote, makeshift runway near Kebri Dahar alongside two men transporting and selling khat.

What I hadn’t realised until I returned to Addis Ababa was that even though they had tried to disguise me as a French water engineer, they had mistakenly added my British nationality to my documents.

After an hour or so of waiting with the Khat dealers, and then being randomly searched by random soldiers who were passing by, I was picked up by some local Somali workers, and then I managed to hide away with a group of wonderful French NGOs from ACF with the additional assistance of a number of Somali youths, who all looked after me.

After being ambushed by Ethopian soldiers deep in the African bush, being constantly spat at wherever I went by random transit Somali men, and being caught up in the middle of a number of scary nomadic tribal skirmishes, as well as having to be locked away every night with the other French workers, I eventually managed to catch a plane back to Addis Ababa after an emotional and harrowing week of feeding stations and dying children.

A few weeks after I left, three of my co-workers were kidnapped by the ONLA and thankfully later released unharmed.

At the time, the Ogaden National Liberation Front (ONLA) fighting meant that the region was a no-go zone for British and American workers, though a single French NGO, Action Contre La Faim (ACF), was active in this area and had ventured further than Gobe, where all the other NGOs were based. Now I was to join them.

ACF’s aim was to reach the nomadic tribes that lived and roamed the Ogaden plains. So, the only way for me to access this part of the Ogaden was to obtain some forged paperwork. My new paperwork and ID identified me as a French water engineer called Sebastian—and after six separate storm-dodging flights, I was dropped off on a remote, makeshift runway near Kebri Dahar alongside two men transporting and selling khat.

What I hadn’t realised until I returned to Addis Ababa was that even though they had tried to disguise me as a French water engineer, they had mistakenly added my British nationality to my documents.

After an hour or so of waiting with the Khat dealers, and then being randomly searched by random soldiers who were passing by, I was picked up by some local Somali workers, and then I managed to hide away with a group of wonderful French NGOs from ACF with the additional assistance of a number of Somali youths, who all looked after me.

After being ambushed by Ethopian soldiers deep in the African bush, being constantly spat at wherever I went by random transit Somali men, and being caught up in the middle of a number of scary nomadic tribal skirmishes, as well as having to be locked away every night with the other French workers, I eventually managed to catch a plane back to Addis Ababa after an emotional and harrowing week of feeding stations and dying children.

A few weeks after I left, three of my co-workers were kidnapped by the ONLA and thankfully later released unharmed.